By Marshall Bwanya

HARARE – Each dawn, 15-year-old Thobeka (not her real name) sets off on a 10-kilometre trek along a dusty trail to Thokozani Secondary School in Insiza, Matabeleland South.

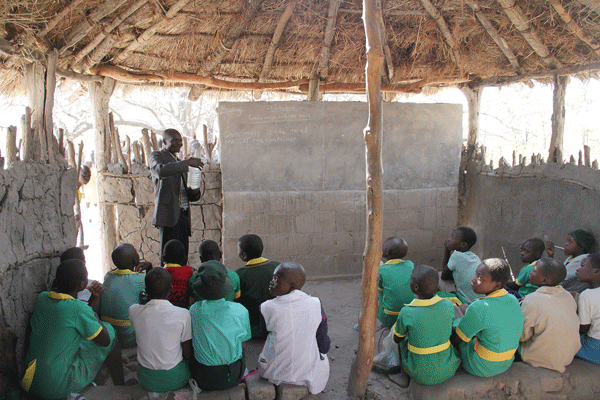

Her destination is a school without water, toilets, electricity, proper accommodation, or enough teachers. Textbooks are scarce. Learning, a daily struggle.

Over 400 kilometres away in Borrowdale, Harare, her peers at the elite St George’s College—a private institution run by the Roman Catholic Church—attend classes equipped with interactive smartboards, digital libraries, and campus-wide Wi-Fi.

The contrast is indeed glaring that one child learns in deprivation, another in digital luxury.

For many Zimbabweans, this is more than inequality. It is injustice.

A system undermined

Education is a pillar of economic progress and national empowerment, yet Zimbabwe’s investment in it has been underwhelming.

Government allocation to education has hovered between 13% and 16% of total expenditure in recent years—falling well short of regional benchmarks.

This underfunding has created cascading problems such as chronic shortages of teaching materials, demotivated teachers, unsafe infrastructure, and widening disparities between urban and rural schools.

The effects are worsened by compounding factors of post-COVID-19 disruptions, climate-induced droughts, high dropout rates among girls, and the marginalisation of children with disabilities.

A recent UNICEF report estimated that over 500,000 prospective learners are out of school, with Mashonaland West registering the highest figures.

The Amalgamated Rural Teachers Union of Zimbabwe (ARTUZ)’s ZIMPULSE report for December 2023–February 2024 found 73% of schools were not allowing pregnant girls to continue learning, and only 18% were fully implementing the inclusive policy.

Urban privilege, rural despair

While urban schools grapple with overcrowding and resource constraints, rural institutions are in crisis.

Many lack basic infrastructure and trained staff.

Nyangambe Turf Primary School in Mwenezi, Masvingo, operates with just two classrooms, no staff housing, and inadequate sanitation.

Teachers and pupils depend on a borehole 700 metres away for water.

At Zvomwoyo Secondary School in Buhera, electricity remains a dream, despite power lines running just 30 metres from the nearest classroom block.

On the other hand Rusere High School in Zaka, Masvingo lacks enough benches and desks for its 800 learners.

Some students walk up to 20 kilometres daily to attend classes. Those from Dzikamai village travel between 9 and 12 kilometres.

At nearby Panganai High School, learners face similar hardships. Many walk 16 kilometres to school, often arriving late and exhausted.

Lessons are missed due to high absenteeism, and some students sleep through classes. Wildlife straying from the Devuli Range adds to safety concerns.

The situation is no better in Nyanga, Manicaland. At Samanyika Primary School, all classroom blocks were condemned in 2023.

Since then, only one new block with three classrooms has been built.

ARTUZ secretary general Robson Chere has called on the government to establish a dedicated education fund to address inequalities between rural and urban schooling, ensuring that learners in marginalized communities receive the same quality of education as those in cities.

“Government must set aside an Education fund specifically for the rural education which will be meant to bridge the gap between rural and urban education.

“Such that learners in the marginalised communities can be able to access the same quality education access as their urban counterparts,” said Chere.

This infrastructure crisis is most acute in Matabeleland provinces.

Despite a slight national rise in the Grade 7 pass rate from 45.57% in 2023 to 49.01% in 2024, schools in districts such as Binga, Tsholotsho, and Gwanda reported zero pass rates.

In some cases, cultural marginalisation has been attributed for deepening the educational vacuum.

The persistent deployment of non-Ndebele-speaking teachers in Matabeleland has revived debates around post-Gukurahundi injustices.

Khanyile Mlotshwa, a critical studies scholar, argues that the ongoing marginalisation of Ndebele-speaking teachers reflects a broader pattern of cultural suppression in the Matabeleland provinces, which he attributes to the historic 1983–87 Gukurahundi conflict, a legacy he contends persists to this day.

“Gukurahundi continues through other means, among them the fact that Ndebeles cannot teach their own children, even if they are trained and qualified to do so.

“Ndebeles are arrested by Shona people, who speak a language they don’t comprehend,” said Mlotshwa.

“In public government offices, even the private sector, Ndebele people have to deal with non-Ndebele people.

“Gukurahundi now continues, especially in its cultural and economic elements,” added Mlotshwa.

These cases lay bare the entrenched infrastructure crisis in Zimbabwe’s rural schools, an urgent call for targeted, sustained investment to narrow the education gap.

The government’s defence

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education spokesperson Taungana Ndoro insists the government is tackling disparities through programmes such as the Public Sector Investment Programme (PSIP), rural teacher incentives, and inclusive education policies.

“The ministry reaffirms its commitment to leaving no child behind. While fiscal constraints persist, we leverage partnerships, community involvement, and policy innovation to drive change,” said Ndoro.

Ndoro added that under PSIP government was embarking on inclusive education policies, a curriculum overhaul, and rural teacher deployment reforms.

“We are rehabilitating dilapidated schools and constructing new classrooms, prioritizing rural and marginalized areas,” he said.

He cited collaborations with NGOs like UNICEF and Plan International to provide solar-powered classrooms, boreholes, and sanitary facilities.

Ndoro said new schools are now being designed to meet disability-friendly standards, and Special Needs units are being established across the country.

To ease access in remote regions, satellite schools and community transport schemes like bicycle pooling are being piloted.

Teachers, Ndoro said, are receiving training in inclusive education, supported by assistive technologies such as Braille and hearing aids.

However, critics like ARTUZ president Obert Masaraure, argue these are “cosmetic reforms.”

“Over 80% of connected schools are not using their bandwidth because of sustainability issues,” said Masaraure.

“While some schools may have power lines, many lack bulbs or even fittings. This is what we call cosmetic progress.”

A crisis of learning, a failure of leadership

Zimbabwe’s 2024 Early Learning Assessment found that 25% of Grade Three learners are unable to read or write proficiently, an early warning of long-term systemic failure.

The minister of Primary and Secondary Education Torerayi Moyo, recently launched the End Learning Poverty for All in Africa (ELPAF) campaign to reverse the trend, but its success depends on closing the rural–urban gap.

Opposition leader Linda Masarira of the Labour Economists and Afrikan Democrats (LEAD) blames the crisis on state neglect.

“What we are witnessing is not an accident. It is a systematic disregard for public education, driven by greed, mismanagement, and misplaced priorities,” she said.

Masarira cited findings from PTUZ leader Takavafira Zhou, who reported that 15,000 teachers are resigning annually due to poor pay and recruitment corruption,leaving more than 50,000 teaching posts vacant.

“In some cases, one teacher is responsible for as many as 65 pupils… This is not education. It is state-sponsored educational collapse,” said Masarira.

A broken profession

Many teachers, demoralised by low salaries and poor working conditions, have turned to side businesses or opened private schools.

ARTUZ deputy secretary Munyaradzi Masiyiwa warned that even urban learners are not immune to the system’s decline.

“There’s a mistaken assumption that urban schools are adequately equipped,” he said.

“Many learners attend extra lessons not by choice, but because formal classroom teaching is insufficient.”

In cities, the shortage of secondary schools has left many children stuck after primary school.

The growing presence of private schools has also exacerbated inequality.

“Most private schools demand monthly fees many parents cannot afford. What happens is that a child will only attend school in the months when fees have been paid.

In a year where a learner is supposed to attend all three terms, some will attend only one or two and no one follows up, because private schools operate as businesses,” said Masiyiwa.

He further highlighted a troubling transition gap: “When you compare the number of primary schools to secondary schools in urban areas, there’s a steep drop.

Many learners finish primary education but don’t proceed to secondary level simply because there aren’t enough schools, funds and resources.

Beyond Rhetoric

While some community-driven solutions, like parent–teacher associations, solar school initiatives, and digital literacy pilots are bearing fruit, these efforts remain too fragmented to offset systemic collapse.

Rebuilding Zimbabwe’s education system will require more than slogans or denial.

It will need accountability, reform, and an honest reckoning with the injustices etched into every chalkboard crack and every child’s abandoned desk.

For learners like Thobeka, the future hinges not on empty promises but on concrete change: repaired classrooms, fair wages, inclusive policies, and genuine support.

Until then, the chalkboard remains cracked, and the educational future of rural learners hangs in the balance.